An interview with Wesley A. Fisher on the restitution of Nazi-looted art

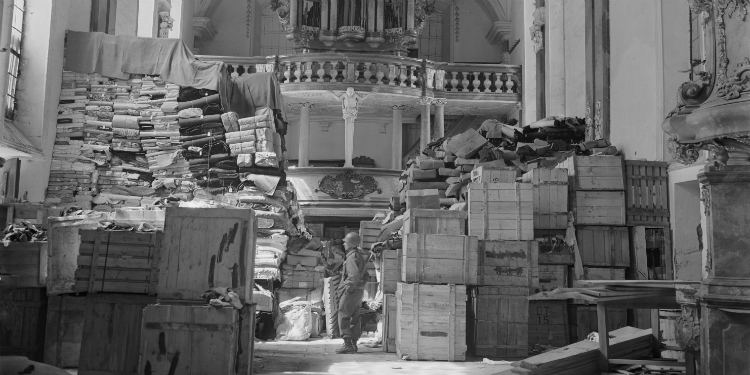

Nazi looted art. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Wesley A. Fisher is the Director of Research at the World Jewish Restitution Organisation (WJRO) and the Conference on Jewish Claims Against Germany, which conduct a comprehensive program toward the restitution of Jewish-owned art and cultural property lost and plundered during the Holocaust. Specialised in the matter of cultural property and looted art, Wesley A. Fisher makes sure information about the provenance of artworks is made available, and also works toward a claim process in all countries, establishing their general structure of the laws and procedures, through negotiations with the governments of Europe. At the Washington Conference on Holocaust Era Assets in 1998, 44 countries endorsed the Washington Principles – a series of guidelines – which call upon governments and museums to ensure that there is a just and fair solution to the issue of looted art. On 25 June 2015, the WJRO released a report concerning current approaches of the United States to Holo caust-era art claims, demonstrating that major U.S. museums have recently been asserting defences to avoid resolving on the facts and merits claims by Holocaust victims and their heirs for the restitution of art pilfered by the Nazis. Art Media Agency had the chance to speak with Wesley A. Fisher to discuss his work at the WRJO and the impacts restitution can have on the global art market.

Can you tell us more about WJRO’s projects to provide provenance information on Nazi-looted art?

The WJRO has worked a lot on unifying and providing access to scattered complex records, such as those of the Einsatzstab Teichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the main Nazi agency responsible for looting Jewish-owned cultural valuables outside of the Reich. These records include hundreds of thousands of lists of artworks, Judaica, books and archives stolen by the Nazis, found in 29 archives in ten different countries. The WJRO has managed to reconstruct them and put the records online, to help individuals determine if an artwork was purloined. At the WJRO, we’ve also created a database of art objects that were processed at the Jeu de Paume by the Nazis in Paris; the only database which shows who things were taken from and what their eventual state was. This particular database has been very useful for the task force in charge of investigating the Cornelius Gurlitt collection in Munich and the MNR collection cases for example.

In 2014, you released a report on the progress of the 44 countries that endorsed the 44 Washington Principles and the 47 countries in the 2009 Terezin Declaration. How do you explain the different progress made by these countries?

When reviewing these countries, we saw that only one third of the countries made clear progress in implementing the Washington Principles and the Terezin Declaration. The majority have done very little, like Italy, while other countries have done quite a bit, such as The Netherlands, Germany, and Austria. There is no international law in the plundered art area; as a result, countries have followed their own internal legal systems and their own political inclinations. It was only in the 1990s that perpetrator countries-like Italy, France, Germany and Austria – began to look seriously at their history, while countries such as Hungary, Italy and Russia have still not reviewed their actions during WWII. Generally, these countries have made very little progress. But there are also countries, like Switzerland or Spain, who don’t consider themselves to be involved in this history, when in fact, these countries were used by the Germans as transit countries, or a place where they could market the art.

What prompted you to release your report on the United States last June?

The WJRO issued this report because after a long period of time where museums handled things ethically, there has been a series of museums that started going to court, using technical defences, such as the statute of limitation, that were not in the spirit of the Washington Principles and were not in accordance with the guidelines of the American Alliance of Museums (AAM). This prevented claimants from getting a review of their situation, based on the facts and the merits. Also, in the United States, in contrast to Europe, most museums are private, and there are no ministries of Culture. Therefore, there is no clear authority to force museums to act one way or the other. In our report on the United States, we reviewed the legal evidence of the museums that have not followed the Washington Principles and the standards set by the AAM. With this report, we urge museums to adhere to the AMM and Washington Principles and insist there should be legislative change.

What type of legislative change is needed?

What happens in the United States, is that U.S. museums use the statue of limitation, which means that after a certain period, you cannot get the artwork back. The museums – because they are private – can refuse to render certain artworks by invoking the statute of limitations. What we need, is a change whereby the statue of limitations begins to run only when the artwork is discovered. Over the last decade in the United States, there has been a long battle about this issue.

Can you tell us about your collaboration with local governments in Europe?

We work with a number of local governments in Europe, but the extent to which countries are willing to collaborate differs from country to country. At the moment, we are working with Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia; Serbia is trying to become a member of the European Union and sees this as part of what she needs to do for that purpose. Also, in Serbia and Croatia, there is a rather specific problem that they have artworks that were stolen in Western Europe – primarily in France – that are currently on display in their museums. This is due to fraud perpetrated against the Monument Men, the American soldiers who were handling misappropriated art after the war. In Slovenia, they just haven’t done the research, so the investigation remains an open matter. In other countries there are other situations: Hungary has not opened its archives today, and seems reluctant to deal with this matter. In France, the problem is not enough work has been done on the museum collections, a nd, while it has made compensations to people, it has restored very little.

What are the claimants’ intentions and do you keep track of what happens to the reinstated artworks?

The press likes to discuss very expensive paintings, and make this a money issue. But in fact, the vast majority of the artworks involved are not worth that much and are usually the only link that people have with their family’s history. These are pieces of art that are part of a genocide, and every family that is coming forward to claim an artwork, is a family that has lost people to the killings. In some instances, money may play a role, but usually Jews try to stay away from that because it’s one of the stereotypes about them. In many cases there is a settlement where the museum in question get to keep the piece. Sometimes it’s a settlement that simply involves recognition and the museum puts a plaque next to the piece explaining the ownership history. Other times artworks will rotate between family members, and sometimes, when it is sold on the market, it may be sold to another museum, making it available to the public. If you look at the most famous instances of this, like Robert Lauder’s purchase of the portrait Adele Bloch Bauer I, he did not purchase it for himself, but for public viewing in Austria and then New York City. Essentially the question is, does the government have the right to go into people’s homes, take paintings off the wall and put them in museums, pay the people nothing and then kill them? Neither the killing, nor the theft is acceptable.

Today, we are seeing more and more stolen artwork on the art market. How do you explain that?

More and more of these items come to the surface because the generation that initially stole or bought them as good faith purchasers, is dying out and the artworks are put on the market. We also hear more about these cases because people are becoming more and more concerned that the artwork they want to purchase comes from a good source, and has a clean ownership history, in order for the artwork to retain its value. In the art market, artwork has become a major investment, and people don’t want an investment that is endangered. Sotheby’s and Christie’s both have large departments dealing with provenance research in which they review the ownership history of artworks brought to them before sale. They want to keep their reputation clean and don’t want to be seen as an auction house that sells stolen goods. That should be the case of private art dealers, but unfortunately, much of the art market works in secrecy and in general it is very hard to find a stolen p ainting.

How do you think these restitution cases impact the global art market?

The restitution of art has often brought major artworks into the art world. Also, it appears from recent auctions, that artworks that have been stolen and then restored, are increased in value by that history. The works from the Gurlitt collection for example, were actually sold for more money as a result of that. Today, provenance history is becoming more and more part of the nature of the artwork, although it is not generally taught in art history or museum studies.

How do you explain the sudden attention that the restitution of looted art is getting?

Really, until the 1990s, art looting was not a major topic because the big issue, for the Jewish people, was to help survivors get back on their feet and move on with their lives, and supporting them financially because they had lost everything. Still today, a number of Holocaust survivors live in poverty, including in the United States, Israel and Eastern Europe. The theft of art was thus not discussed because it was complex and because there were other, more urgent problems. Today, at the WJRO we ensure that these cases of art restitution can go forward: As the survivor generation has been passing, the artworks have become more important, because they are the only link to the family members they have lost. WW II represents not only the largest art theft in history, but also a principal example of what we need to fight against today in countries such as Syria, Tunisia, Bosnia and Cambodia. In that sense, it’s of great interest and importance.